Are high auto re-enrollment rates in the ACA's State-based marketplaces a problem? Take II

More frequent auto re-enrollment in SBMs appears to be at least partly a result of better information and lower benchmark volatility in the SBMs than in HealthCare.gov states

My last post flagged dramatically different rates of “active” health plan renewal and autorenewal in the 33 states using the federal ACA marketplace, Healthcare.gov, compared to the 18 states (including D.C.) that run their own marketplaces. This post take a second run at whether the high autorenewal rates in the state-based marketplaces (SBMs) are problematic.

In HealthCare.gov (the “FFM,” or federally facilitated marketplace), 72% of renewals in the Open Enrollment Period 2023 were active, meaning the enrollee logged into the marketplace, updated their personal information, and affirmatively chose either to remain in last year’s plan or choose a new one. In the SBMs, just 28% of renewals were active; 72% of returning consumers were auto re-enrolled.

Auto re-enrollment can be dangerous, because 1) enrollees’ personal circumstances that affect subsidies — their income and the family members seeking coverage in the exchange — may change; 2) an enrollee’s current plan’s premium may rise in the coming year; and 3) most unpredictably, the benchmark (second cheapest silver) plan against which subsidies are set can change. If the coming year’s benchmark plan has a lower premium than the current year’s, subsidies shrink, since enrollees pay a fixed percentage of income for the benchmark plan. If the enrollee’s premium rises and the benchmark falls, it’s a double whammy.

I therefore presented high auto re-enrollment rates as a troubling feature of the SBMs, and maybe in some cases they are. But there are also differences in SBM and FFM practice that may make auto re-enrollment more viable for more enrollees in the SBMs.

Enrollees get better information earlier in at least some SBMs

Most strikingly, independent health insurance broker Sheron Sidbury, who serves clients both in Maryland, which runs an SBM, and Virginia, which uses HealthCare.gov, explained in a lengthy Twitter exchange that in Maryland, plans and prices are posted on October 1, well in advance of the Nov. 1 kickoff of Open Enrollment. In Maryland, Sidbury explains:

This is just based on my personal experience with SBE and FFM. I have many passive enrollments in my book of business. Passive enrollment doesn’t mean no action is taken in my case with my clients. MD post plans, prices and the actual next year subsidy loaded by October 1.

By Oct2 everyone is messaged with their new plan, prices and a recommended comparison of their current plan, if it no longer the best choice. In more than 90% of the cases with the 94%CSR [Silver,] Gold and Bronze clients their current plan has always been the best choice. 100% auto renew [if Sidbury so recommends].

FFM states always late to the game. Companies (and agents) don’t have access to new subsidies thus send inaccurate renewal notices based on current year subsidy. Due to incorrect prices and wild benchmark swings many more switch plans each year to maintain affordability.

The crucial difference described here is that the Maryland exchange sends out a renewal notice that includes a subsidy estimate and premium estimate for renewal of the enrollee’s current plan. That estimate is based on the most recent income and household information the exchange has. While the estimate’s accuracy is contingent on no personal changes by the applicant, it’s based on the new (coming-year) benchmark and plan premium. GetCoveredNJ, the New Jersey marketplace, also sends out an estimate like this, though it goes out in the first week of November, rather than September 30 as in Maryland.

The federal marketplace, HealthCare.gov, does not provide this information to enrollees. It sends out a renewal letter, but with no specific information as to subsidy and premium in the coming year for the enrollee’s current plan. Instead, the FFM requires insurers to send renewal letters prior to November 1 (first day of OEP), with an estimate of premium in the current year. But the insurer’s letter, while it provides the plan’s new premium (before subsidy) in the current year and an estimate of what it will cost net of subsidy, bases the subsidy estimate on the prior year’s benchmark. Thus it is nearly always inaccurate, as Texas broker Jennifer Chumbley Hogue, CEO of KG Health Insurance, reports:

The letters are going to be wrong. They have to printed and sent before new subsidy information is even available

Accordingly, Hogue adds,

even my “no changes” renewals are considered active, with a new eligibility letter generated. I have zero confidence in FFM passive renewals, plus clients getting a new eligibility letter with accurate subsidy information is always a good idea.

To sum up: enrollees in the Maryland, New Jersey and other (not, I think, all) SBMs get a renewal estimate from the exchange that is accurate insofar as the enrollee has no changes to make as to the income and family composition reported in the prior year application. HealthCare.gov enrollees get no such estimate from the exchange, but prior to OEP they get an almost invariably inaccurate estimate from the insurer. Thus enrollees in at least some SBMs can let autoenrollment go forward on a reasonably solid informational basis. HealthCare.gov enrollees can only get an accurate sense of what their current plan will cost in the current year by logging on.

SBMs send renewal letters with updated subsidy and premium information not only in Maryland and New Jersey but, as far as I’ve been able to confirm so far, in New York, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Massachusetts.* Covered California’s renewal letter (linked to in the open enrollment toolkit available here) appears to direct the recipient online to find updated subsidy and premium information (as any enrollee can do on any exchange), but that’s not entirely clear, as the sample renewal letter shows different texts for enrollees in various situations.

In SBMs, less benchmark volatility

A second key factor is one that I touched on in my prior post but didn’t pay enough attention to (Tara Straw of Manatt Health pointed it out to me). SBM states tend to regulate their health insurance markets more actively than do states that rely on the FFM, and on average, have not allowed as wild a proliferation of plan offerings in recent years. That means that benchmarks and therefore subsidies are more stable (on average) than in the FFM, and so in SBMs, switching plans is less often imperative to avoid a major premium spike.

Sidbury reports a dramatic difference on this front between Maryland, where most clients authorize her to let autorenewal go forward, and Virginia, where she estimates that fewer 20% of her clients autorenew. In a phone conversation, Sidbury told me, “In Virginia, I always need to update because benchmarks are all over the place. I had some clients whose current plan premium went from $0 to $300. There are nine insurers in the state (not in every area), and because of all the entering and exiting and just all the craziness, you can’t really auto-renew.”

CMS recognizes that the wild proliferation of plans in the FFM in particular in recent years is a problem, as discussed in this post (note Centene/Ambetter’s 15 silver plans on offer in Chicago). Having re-introduced a non-mandatory standard plan design for 2023, the agency proposed a rule to limit the number of non-standard plans a given insurer could offer in 2024 — two for each provider network type at each metal level — and then, in its final rule, watered down the standard down to four in each category. CMS estimates that the rule will only modestly reduce the number of plans available in the average rating area in HealthCare.gov states, from 114 to 90.

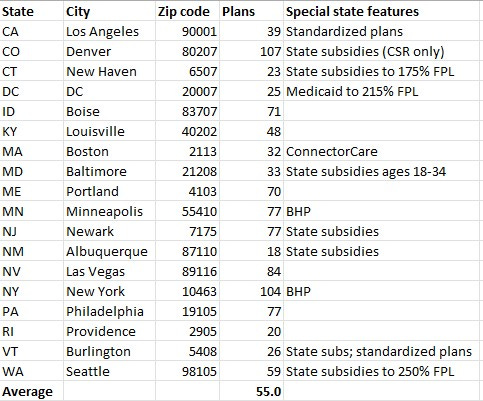

While I lack means to derive an average number of plans available in SBM rating areas, I have tallied the plan total available in the largest city in each SM state — visiting each state exchange, and using the plan preview tool to view plans in each city (by zip code). Large cities tend to have more plan on offer than do smaller rating areas, particularly rural ones. In 2023, in FFM cities, Chicago has 137 plans on offer. Miami has 224. The SBM large-city average is 55. As all plans in California conform to a standard design for each metal level, Los Angeles has all of 39.

In the far-right column of the table below, I’ve noted state marketplace features that tend either to reduce benchmark volatility or, in the case of supplemental state subsidies, reduce the risk of sharp premium increases simply by increasing total subsidies. Basic Health Programs (BHPs) in New York and Minnesota take the lowest-income (and so probably lowest-information) enrollees out of the marketplace. In Massachusetts, ConnectorCare, a market composed of low-cost standardized plans offered at incomes up to 300% FPL, also takes most of the financial risk out of autoenrollment. “In general, we do find that even our active enrollees choose the same plan that we passively mapped them to. Our highly standardized and limited plan shelf likely mutes plan changes—only people looking for a different tier or provider network are likely to switch,” the Massachusetts Health Connector said in a statement.

Number of health plan offerings in SBMs’ largest cities**, 2023

In my last post, with respect to the large difference in autoenrollment rates in the FFM vs. the SBMs (28% vs. 72%), I wrote, “My first thought, staring at the numbers in the first table above, was that the difference in active reenrollment rates between HealthCare.gov and SBM states must be at least in part a statistical illusion.” That’s not literally the case, CMS confirmed to me. But the last part of CMS’s statement is worth a second look (my emphasis):

The definition of auto re-enrollment is the same between states using HealthCare.gov and states with State-based Marketplaces (SBMs). In both cases, consumers who actively make a plan selection in their previous year’s plan or their crosswalked plan are counted as active re-enrollees. Different outreach and operational strategies may explain some of the difference in the auto re-enrollment percentages between HealthCare.gov and SBMs.

The differences in outreach and operational strategies are major, as are the differences in plan menus between the FFM and SBM states (taking each as a whole, albeit with major differences within each group as well). In many if not all SBMs, enrollees have less reason to switch plans and more accurate information as to what they will pay if they auto re-enroll.

—

* Re SBM renewal letters, for New York, see slide 15 here. For Minnesota, the MNSure FAQ spells out: “You can view your updated eligibility for next year, including any updated tax credit amounts and cost-sharing reductions, on the eligibility renewal notice that you receive from MNsure.” For New Mexico’s bewellnm, I have the personal assurance of someone who knows procedures there that the exchange sends enrollees a net-of-subsidy estimate based on the current benchmark. In Massachusetts, Heath Connector spokesperson Jason Lefferts explains [added 5/1, 1:00 P.M.], “We send the member a renewal notice in October that includes the enrollee monthly contribution, net of subsidy, as well as the APTC amount that was applied calculate it. These amounts are based on actual premiums and reflect the cost for the plan into which the member will be automatically mapped unless they shop and change plans during open enrollment.”

** The plan total listed for New York is a little uncertain, as plans with and without adult and children’s dental coverage are listed separately. (Commercial e-broker HealthSherpa, which is always accurate in FFM states (where it can execute enrollments) but not 100% accurate in SBM states, lists 90 plans in New York.)

Horn & Hardart/Lumitone Photography, New York, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons