Massachusetts poised to extend ConnectorCare's low out-of-pocket costs to 500% FPL

A budget provision vetoed by Governor Baker this past summer may become law under Governor-elect Maura Healy

Predating and existing alongside the ACA marketplace, Massachusetts implemented and has maintained a better system.

At incomes up to the 300% of the Federal Poverty Level, Massachusetts applicants who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid are offered a standard, easily comprehensible benefit package with low premiums and out-of-pocket costs. That contrasts with the ACA's bewildering array of sometimes more than 100 plans in four metal levels, each offering a smorgasbord of copays and coinsurance, often with high but Swiss-cheese deductibles to which many services are not subject.

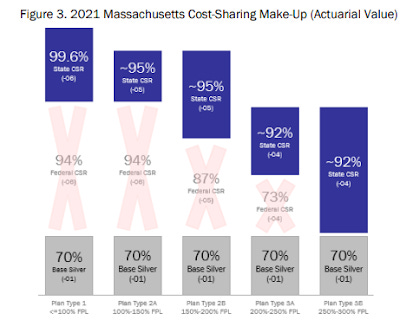

As measured by actuarial value -- the percentage of the average enrollee's annual costs* the plan is designed to pay -- ConnectorCare offers more generous coverage than the ACA's benchmark silver plans (which are enhanced by Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies at incomes up to 250% FPL) at every income at which it's available. The AV difference is nominal at the 100-150% FPL income level, pronounced at 150-200% FPL, and enormous at 200-300% FPL, as illustrated below (via a 2021 program overview). Equally important, enrollees are not lured by bronze or gold plans with radically higher out-of-pocket exposure.

The higher AVs in ConnectorCare translate into much lower deductibles and annual maximum out-of-pocket costs for enrollees -- particularly at incomes in the 200-300% FPL range. While marketplace enrollees in other states may offer plans with lower premiums than ConnectorCare's at incomes over 150% FPL, those low-premium plans will usually expose enrollees to much higher out-of-pocket costs. (An exception is when the lowest-cost silver plan is priced well below the benchmark (second cheapest) silver plan, in which case an enrollee in the 150-200% FPL range may get an 87% AV silver plan for zero premium or close to it.)

ConnectorCare's benefit structure is similar to that of the Basic Health Programs for low income residents established by Minnesota and New York under an ACA provision enabling states to establish such programs. ConnectorCare has two major advantages over the BHPs, however.

First, its benefits extend to enrollees with income up to 300% FPL, whereas the BHPs are required by statute to cap eligibility at 200% FPL. Second, ConnectorCare plans are in a single risk pool with plans offered to Massachusetts residents with incomes over 300% FPL, which follow the ACA's standard marketplace structure. Accordingly, the plans sold to higher-income enrollees benefit from high takeup of ConnectorCare plans by healthy low-income enrollees, which pushes down premiums for the unsubsidized. That matters in Massachusetts, where a third of marketplace enrollees are unsubsidized.

Coming soon: Lower out-of-pocket costs at higher incomes?

The single risk pool also makes it feasible for Massachusetts to extend the ConnectorCare benefit structure to higher incomes without cannibalizing the marketplace for those who don't qualify for ConnectorCare. The state almost did just that in 2022, and very well might do it this year.

In July, the state legislature passed a budget that included a two-year pilot program to extend eligibility for ConnectorCare to enrollees with income up to 500% FPL ($67,950 for an individual and $138,750 for a family of four in 2023).

Health Care for All Massachusetts (HCFA), a nonprofit that advanced the proposal, claimed in a press release responding to the veto, "The pilot program is fully paid for by leveraging savings the state has accrued over the past two years from enhanced federal insurance premium subsidies." That is, while Massachusetts had been funding "wraparound" subsidies that make ConnectorCare possible since the ACA's inception, the boost to federal subsidies provided by the federal American Rescue Plan Act in much of 2021 and all of 2022 reduced the state's contribution, which in 2019 came to $67 per ConnectorCare enrollee per month. With Democrat Maura Healy taking office as governor in 2023, passage and enactment of the two-year ConnectorCare expansion seems likely.

The vetoed budget provision (see Section 133, p. 415 here) stipulates that ConnectorCare provide "at least" 90% AV to the newly eligible enrollees in the 300-500% FPL income bracket -- that is, only marginally lower value, if lower at all, than offered by ConnectorCare plans now available at 200-300% FPL. Those plans have a single-person maximum out-of-pocket limit (MOOP) limit of just $1,500 for medical expenses and $750 for drugs. By contrast, the bronze and silver plans in which 95% of current Massachusetts enrollees in the 300-500% FPL bracket are enrolled in generally have MOOPs of $9,100 ($7,500 for HSA-compatible plans). Oh, and ConnectorCare plans have no deductibles. Moreover, the highest co-pay in the current highest income bracket is $250 for inpatient hospital care.

In 2022, 41% of Massachusetts enrollees in the 300-500% FPL income range selected bronze plans (60% AV), 54% enrolled in silver plans (70 AV), and 5% chose gold plans (80% AV). Massachusetts' marketplace for higher-income enrollees (those not eligible for ConnectorCare) offers standardized and non-standardized plans, all prominently marked as such. The deductibles on standardized plans are far lower than national averages, and the non-standardized plans more or less follow suit. In 2023, standard plan deductibles in Massachusetts were $2,850 for bronze, $2,000 for silver, and $0 for gold, compared to national averages in 2022 of $7,051 for bronze, $4,753 for silver (without CSR, unavailable in this income bracket), and $1,600 for gold.

Given the relatively low standard deductibles in the current Massachusetts market (substantial as they are in bronze and silver), the chief advantage for wealthier enrollees in switching to ConnectorCare would be in MOOP exposure, enabled in part by much lower copays (3-4 times lower in 2021) for expensive services like inpatient hospital care and outpatient surgery. All told, providing a 90% AV plan with no deductible at anything near benchmark silver cost (that is, in the current ACA subsidy schedule, between 6% and 8.5% of income at 300-400% FPL, and 8.5% of income at 400% FPL and above) would constitute a very substantial additional subsidy in this upper middle class income bracket.

HCFA, which commissioned an actuarial study of the effects of extending the program to the 300-500% FPL income bracket, estimates that 37,000 enrollees would benefit. In 2022, 32,000 enrollees in Massachusetts reported income between 300% and 500% FPL, according to CMS's state-level public use files, and 83,000 enrollees did not report income. The estimate of 37,000 beneficiaries does not seem out of line.

You might think that extending heavily subsidized, standardized, 90%-plus AV coverage all the way to 500% FPL would wipe out the individual market still available at higher incomes, but in Massachusetts that is not the case. In 2022, more than a third of enrollees in the state exchange (91,000) either reported income over 500% FPL or did not report income at all. As noted above, if all or most of 32,000 enrollees in the 300-500% FPL income bracket switch to ConnectorCare, that will not affect insurers that participate both in the high-income market and in ConnectorCare, as an insurer's enrollees in ConnectorCare and the higher-income marketplace are in a single risk pool. While some insurers currently serve only the high income market, as of 2024, all insurers that sell in that market will be required to participate in ConnectorCare as well.

Massachusetts has long had the lowest uninsured rate in the nation -- just 2.5% in 2021. Thanks to ConnectorCare, and practices noted in the appendix below, the state also works effectively to reduce underinsurance for its marketplace enrollees, which in most states is rife among those not enrolled in high-CSR plans (i.e., silver plans at incomes up to 200% FPL). The 300-500% FPL bracket may not be the most needful -- but exposure to MOOP caps of $9,100 is a serious liability in that income range. A state committed to affordable healthcare for all would do well to reduce that exposure.

Appendix: The history, financing and unique advantages of ConnectorCare

ConnectorCare mostly preserves the benefit structure of the Massachusetts near-universal coverage scheme enacted in 2006, the ACA's precursor. When the ACA was enacted with a less-generous and more loosely structured benefit structure (albeit subsidized to incomes up to 400% FPL, in contrast to Massachusetts' 300% FPL subsidy cap), Massachusetts had to get creative to preserve its superior benefit package. ConnectorCare plans are technically silver plans with a baseline 70% AV, enhanced first by federal Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) subsidies at incomes up to 250% FPL and then by state-funded "wraparound" subsidies that enable the higher-AV ConnectorCare benefit structure.

Massachusetts' original plan, signed into law by Governor Mitt Romney in 2006, was funded in part by a federal Medicaid 1115 waiver that had been granted to reduce the state's uninsured population. Successor waivers still partly fund the wraparound subsidies that enable ConnectorCare. Additionally, according to the 2021 program overview cited above, "State funding for ConnectorCare CSRs and premium subsidies is held in a dedicated trust, the Commonwealth Care Trust Fund (CCTF), which collects revenue from cigarette taxes, state individual mandate penalties, and employer assessments."

To keep costs low, the Massachusetts individual market enjoys some unique or near-unique advantages. Massachusetts imposes a higher minimum medical loss ratio (MLR) -- the percentage of premiums an insurer is required to spend on enrollees' medical expenses -- than the federal standard imposed by the ACA, 88% compared to 80%. States have to apply and qualify to participate in the ConnectorCare market, and competition among ConnectorCare insurers to offer the lowest-cost plan is intense, as that is the plan offered at the advertised cost, ranging from $0 to $130 per month in the five different income levels (though the state, seeking to preserve real choice in the ConnectorCare market, covers most of the difference between the cheapest and most of the more expensive offerings in each market). The state also maintains a merged individual and small group market, one of only three states to do so. Finally, as Louise Norris notes in her overview of the MA marketplace, "The Health Connector is an active purchaser exchange, which means the exchange determines which plans are offered for sale."

----

* Actuarial value, purportedly the percentage of the average enrollee's costs paid by the plan, is calculated according to a formula provided by CMS. But the highest-cost enrollees skew the average, as a billionaire walking into a bar skews the average income of those present. For example, an enrollee in a 60% AV plan who suffers a serious accident may max out a $9,000 MOOP cap while the plan pays, say, $120,000 for multiple operations and in-patient care. Thus a bronze plan purporting to cover 60% of costs for the “average” enrollee may have a deductible of $8,000 and coinsurance of 50% for most services.