Shopping in the ACA marketplace: A strategic guide

Ding! The ACA's tenth annual Open Enrollment Period kicked off on Nov. 1, for enrollment in coverage activated on Jan. 1, 2023. The premium subsidy boosts provided by the American Rescue Plan Act for 2021 and 2022 are still in force, extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act enacted in August.

For everything you've always wanted to know about how the ACA marketplace works and what's on offer, Louise Norris and Charles Gaba offer definitive guides. What I have in mind here is more limited: a kind of strategic framework for prospective enrollees at different income levels.

The ACA is means-tested to a fault. Six income brackets determine not only what percentage of income you'll pay for a benchmark silver plan (or whether you'll be enrolled in Medicaid or, in states that have refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion, get no help at all), but also what kind of coverage is available at that benchmark price and metal level. Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR), a secondary benefit that attaches to silver plans only, is available at three different strengths in three separate income brackets.

Here are some key facts that may be lost in the welter of rules and features that shape ACA benefits.

Small differences in projected income can have a large impact on available benefits.

Income estimates for the coming year are by their nature flexible for many workers.

The Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) benefit that attaches to silver plans only makes a hash of the ACA's metal levels.

Health plans' annual maximum out-of-pocket (MOOP) limits vary a lot -- and matter a lot.

For people of some means, plans linked to Health Savings Account (HSAs) can be hard to pass up.

Let's take these one at a time. As I have covered most of these points in more detail in prior posts, here at xpostfactoid and at healthinsurance.org (an ACA information source distinguished by its principle author, the esteemed Louise Norris), I've provided links to many of these posts below.

1. Small differences in projected income can have a large impact on available benefits

To determine an applicant's benefits, the ACA application translates the applicant's estimate of gross household income in the coming year (subject to a few adjustments) into a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). For some people, an estimate of next year's income is straightforward; for many, especially at low incomes, it's not. It's therefore extremely useful to be aware of various income break points where benefits shift.

A. 100% FPL -- the minimum income required for subsidized coverage in nonexpansion states.

As drafted, the ACA makes Medicaid available to most adults with an income below 138% FPL. In 2012, however, the Supreme Court made that Medicaid expansion optional for states. At present, 12 states have refused to enact the expansion, and in 11* of them, most adults with incomes below 100% FPL get no help paying for any kind of coverage (in a drafting inconsistency, the ACA pegged the minimum income for subsidy eligibility in the marketplace at 100% FPL rather than 138% FPL). The nonexpansion states include population giants Florida and Texas. Nationally, some 2 million adults are stuck in this "coverage gap."

In 2023, the 100% FPL threshold for subsidized coverage is $13,590 for a single person, $18,310 for a two-person household, $23,030 for a family of three, and $27,750 for a family of four. It is near this threshold that uncertainty and flexibility in the income estimate matter most. Just over that threshold, benchmark silver coverage with strong Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) is available free, up to 150% FPL ($20,385 for an individual).

Simple awareness of this threshold may help many enrollees avoid ineligibility for subsidized coverage, as discussed in Point 2 below.

B. 138% FPL -- the upper income threshold for Medicaid in 38 expansion states.

In the 38 states** that have enacted the ACA Medicaid expansion, most citizens and legally present noncitizens with income below 138% FPL qualify for Medicaid (and so are ineligible for marketplace coverage). Medicaid eligibility is determined on a monthly basis -- which means (in expansion states) that if your income falls off a cliff and isn't likely to recover in the short-term, you qualify. The monthly thresholds are $1,563 for a single person, $2,106 for a two-person household, $2,648 for three, and $3,191 for four.

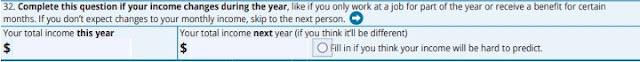

For most people near this income level, Medicaid is probably the best option, as out-of-pocket costs range from zero to minimal. However, marketplace coverage with relatively modest (though larger) out-of-cost exposure and in some cases more robust provider networks is also free to a slightly higher income threshold, 150% FPL. Since marketplace eligibility and subsidy level is calculated on an annual income basis, an applicant may qualify for Medicaid by citing current monthly income, or for the marketplace by estimating annual income. The HealthCare.gov application enables the latter:

There is one particular case in which an applicant might want to stay out of Medicaid. In more than 20 expansion states, any Medicaid enrollee who is over age 55 is potentially ultimately subject to Medicaid Estate Recovery upon their death. If the deceased enrollee owns any significant assets, the state may seek to recover from their heirs the value of all the premiums paid for Medicaid. While most older enrollees who have income low enough qualify for Medicaid may have minimal assets, that certainly is not always the case. I was alerted to this travesty by an elder lawyer who has helped some health insurance applicants avoid Medicaid qualification.

C. 200% FPL -- the maximum income at which strong Cost Sharing Reduction enriches benefits.

At incomes up to 200% FPL ($27,180 for an individual, $36,620 for a family of two, $55,500 for a family of four), CSR, which attaches only to silver plans, raises the value of a silver plan to a roughly platinum level (a bit above platinum at income up to 150% FPL, a bit below at 150-200% FPL). Above the 200% FPL threshold, the value of CSR drops off sharply, and it phases out entirely at 250% FPL. Affordable marketplace coverage, therefore, is far more comprehensive for a single person estimating an income of $27,000 per year than for the same person estimating an income of $28,000 (or, for that matter, $27,200). Strong CSR is a benefit not to be foregone if you are eligible.

At 200-250% FPL, CSR raises the actuarial value of a silver plan -- the percentage of the average enrollee's costs the plan is designed to cover -- only minimally, from 70% (silver with no CSR) to 73%. CSR at this level does reduce the highest allowable maximum out-of-pocket (MOOP) cap from $9,100, the max for plans with no CSR, to $7,250. That can be dispositive in some cases, i.e., for people who suspect or know that they will need enough care to hit the MOOP cap, as MOOP runs high in most non-CSR plans. More often, at incomes above 200% FPL, premium discounts in bronze and gold plans created by silver loading (see below) make those metal levels a better choice.

D. 400% FPL -- never mind! The once and possibly future subsidy cliff

From January 2014 through to March 2021, the ACA's second sharpest subsidy cliff (the coverage gap in nonexpansion states being the first) was the cutoff of subsidy eligibility at 400% FPL. Premium levels vary enormously by state and rise with age. For perhaps 3-5 million people in need of coverage but ineligible for subsidies, coverage was unaffordable, or required as much as 15-20% of income.

The American Rescue Plan Act enacted in March 2021 removed the income cap on subsidies, instead capping premiums for a benchmark silver plan at 8.5% of income at incomes above 400% FPL. The Inflation Reduction Act, enacted in August 2022, extended the ARPA subsidy boosts to 2025. With Republican control of one or both houses of Congress looming, however, the cliff will likely rise again.

2. Income estimates allow some flexibility.

We’ve seen that small differences in income can spell major differences in benefits.

Given the stakes, it’s important to understand that during the ACA’s Open Enrollment Period, which begins annually on November 1, benefits for the coming year are based on an estimate of future gross (pre-tax) income, modified in some cases by deductions.

The estimate is usually straightforward for a salaried adult with one job who's likely to stay in that job for the entire year to come and lacks other significant sources of income. For others, including most low-income people, the estimate is subject to a lot of variables - - and thus allows some wiggle room. That's the case if you're paid by the hour, and/or rely in large part on tips, or work more than one job, or are partly or wholly self-employed. (Self-employment in particular allows for a broad range of deductions, including pension contributions, that reduce the income counted toward the marketplace subsidy.)

If you underestimate your income and take your full subsidy, in the form of an Advanced Premium Tax Credit (APTC) used to pay your premiums as they are billed (you can opt to take only a portion of it in advance for this purpose), you will owe the difference between the APTC you received and the APTC to which you were entitled at tax time in the year following (early 2024 for 2023 coverage).

There is no downside, however, to a good-faith estimate that errs on the optimistic side -- e.g., to get an applicant in a nonexpansion state over the eligibility threshold. If you live alone and estimate your 2023 gross income at $14,000 (a little over 100% FPL), and eventually, your tax return shows it to have been $11,000, your subsidies will not be clawed back, unless the estimate is made with “intentional or reckless disregard for the facts.” And while you may be asked as part of the application process to document your income, your estimate will not be disallowed if outside data sources indicate that your real income is lower than estimated. (If those sources indicate that your income is higher than estimated, the exchange may reduce your APTC.)

For low income applicants in nonexpansion states, knowing the eligibility threshold is crucial. Many if not most have no idea -- and when they're told why they get no help paying for coverage, they're incredulous. Rightly so -- no rational government would disqualify people from help for earning too little. And no one who can credibly hope to cross the income threshold in the coming year (or what's left of the year, for those who enroll outside of OEP) should hesitate to project an income that will enable coverage.

As insurance broker Jennifer Chumbley Hogue, CEO of KG Health Insurance in Murphy Texas, told me when I examined strategies for getting the income estimate over 100% FPL in more detail: “If somebody calls me and they’re on the bubble, I tell them: ‘the state of Texas did not expand Medicaid. That means, if you cannot project $13,000 of income, you do not get any help. So let me ask you: Do you think you’re going to make $13,000 in 2021?’” When the question is put so starkly, it's safe to assume that the answer is rarely "no."

3. CSR makes a hash of the ACA's metal levels.

The ACA marketplace presents a seemingly intuitive plan menu: Plans offered at four 'metal levels' that offer a tradeoff between premium and out-of-pocket costs. At the baseline, bronze plans have an actuarial value of roughly 60%, silver 70%, gold 80%, and platinum (a rare dodo bird in the marketplace) 90%.

But CSR scrambles this calculus. While bronze, gold and platinum plans offer the same benefits to enrollees at all income levels, silver plan benefits vary with income -- a lot. With CSR attached, silver plans have an actuarial value of 94% (at income up to 150% FPL), 87% (at 150-200% FPL), 73% (at 200-250% FPL), and 70% (at incomes above 250% FPL). Stepping back, they are essentially platinum at incomes up to 200% FPL, while generally priced (but oy, not always, see below...) between bronze and gold.

Under the ARPA subsidy regime, silver plans with an AV of 94% are now free to enrollees with income up to 150% FPL (e.g., to more than 40% of enrollees in nonexpansion states), and cost no more than 2% of income for enrollees in the 150-200% FPL bracket. Silver is almost always the best choice at incomes up to 200% FPL.

The metal level structure was further disrupted by silver loading, a pricing practice that began in 2018. In the ACA's first years, 2014-2017, the federal government reimbursed insurers directly for the value of CSR, and insurers accordingly priced silver plans as if their actuarial value were always 70%, the baseline for no-CSR silver. In October 2017, however, Trump abruptly cut this reimbursement off, as a Republican Congress had never authorized the spending for it (though the ACA statute requires it). The move had been anticipated, and regulators allowed or encouraged insurers to price CSR directly into silver plans. Since premium subsidies are set to a silver benchmark, subsidies rose with silver premiums, creating discounts in bronze and gold plans. These discounts have rightly induced enrollees who don't qualify for CSR to leave silver in droves.

Since direct CSR reimbursement had been contested from the get-go (the ACA statute mandated it, but left it up to Congress to appropriate the funds, and Republican-controlled Congresses refused to do that), analysts had long since predicted silver loading effects. In fact, these analysts (e.g., HHS, the Urban Institute, and CBO), anticipated that gold plans would consistently be priced below silver, since silver plans on average (thanks to low-income enrollees who get strong CSR) have a higher AV than gold plans. That mostly hasn't happened, though some states -- now including Texas -- have effectively mandated it.

In a handful of states and localities, gold plans are priced well below the silver benchmark, and so are available for free at incomes up to 200% FPL. In such cases, they may lure low-income enrollees out of high-CSR silver, particularly in the 150-200% FPL income range, where silver plans have nonzero premiums (up to about $45/month for benchmark silver for a single enrollee) and gold plans may not. Gold is usually if not always a mistake at this income level (and bronze always is), largely because of MOOP differences. Which brings us to our next point.

4. MOOP limits vary a lot -- and matter a lot.

By the standards of other wealthy nations, Americans are exposed to an obscene level of out-of-pocket healthcare costs. According to polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 100 million Americans are saddled with medical debt. Debt hits the insured almost as often as the uninsured, according to KFF: 61% of insured adults report medical debt, vs. 71% of the uninsured.

For the insured, debt flows from high deductibles, high copays, and high annual MOOP caps. For the last, the highest allowable, $9,100 for a single person and double that for a family, is the same in the marketplace as in employer-sponsored plans. In the employer market, the average single-person MOOP is $4,355, according to KFF (p. 126 here). Thanks to CSR, the marketplace average may be comparable. But most plans that lack CSR have MOOPs close to the maximum.

While surveys indicate that most Americans don't reliably understand basic insurance terms, I suspect that most marketplace enrollees have a pretty good idea of what the deductible signifies. It's prominently featured in plan overviews and defined via mouseover. It's a ubiquitous term, common to other forms of insurance, and often used as a stand-in for out-of-pocket costs generally.

MOOP is, I suspect, less well understood (it's pretty well demarcated on HealthCare.gov, less so on some state exchanges). But it's arguably as important as the deductible -- and from a catastrophic risk perspective, more important.

MOOP is the primary reason that silver plans are almost always preferable to gold at incomes below 200% FPL, even where gold plans have lower premiums. Up to 200% FPL, the highest allowable MOOP for silver plans in 2023 is $3,000. In 2022, MOOP in silver plans averages $1,208 at incomes up to 150% FPL and $2,591 in the 150-200% FPL, according to KFF. The median MOOP in 2022 for gold plans is $7,500, according to the Commonwealth Fund, and $8,500 for silver with no CSR (close to this year's maximum allowable, $8,700). Bronze MOOP is comparable to silver, with the exception of HSA-compatible plans, discussed below. With some exceptions, choosing a gold plan rather than silver is likely to expose an enrollee in the 150-200% FPL income range to an additional $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs in the event of major injury or illness.

The high MOOP prevalent in gold and no-CSR silver plans also tends to push higher income enrollees into bronze plans. Since no-CSR silver plans often have no significant MOOP advantage over bronze, and silver loading increases the spread between bronze and silver premiums, there's a pretty narrow window in which out-of-pocket savings in silver plans relative to bronze will eclipse the premium difference.

The gravitational pull toward bronze is even stronger for older enrollees. Here's how I explained this while chronicling how my wife and I ended up in a bronze plan this year after exiting employer-sponsored coverage:

Because premiums rise with age, the field tilts further toward Bronze plans for older enrollees. As the premium for a benchmark Silver plan rises, so does the subsidy, since all enrollees with the same income pay the same premium (a fixed percentage of income) for the benchmark plan. As the premium rises, so does the “spread” between the benchmark premium and cheaper plans. While my wife and I would pay $400 a month for benchmark Silver, we can get the cheapest Bronze plan on the market (from the same insurer) for about $10 per month.

Another factor tilting the field toward bronze for prospective enrollees ineligible for CSR is that strange love child of American market fundamentalism, the High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) linked to a tax-favored Health Savings Account (HSA). Most HDHP plans are bronze. Which leads us to...

5. To them with the means to save, more shall be given: The HSA

Long long ago in a galaxy far far away, a deductible above $1,000 was considered a weird, risky exposure, and many health economists (mostly but not exclusively right-leaning) believed that more exposure to higher out-of-pocket costs would cause Americans to avoid unnecessary medical care, shop smartly among providers, and so generate competition that would push down costs.

That theory has been more or less discredited by multiple studies indicating that enrollees faced with high out-of-pocket costs skip necessary as well as unnecessary care. But lawmakers responding to this theory created the HDHP: a plan with a high deductible, no services available until the deductible is reached (the free preventive care later mandated by the ACA is now an exception) and a fixed out-of-pocket maximum.

At present, the statutorily required minimum "high" deductible in HDHPs is a laughably low $1,500 -- below the gold plan average. But most HDHPs in the market place do have high deductibles -- they are bronze plans (there are some silver HSAs). And the statutory MOOP for HDHPs, $7,500 in 2023, is lower than the median silver MOOP in 2022.

For enrollees pushed into bronze plans by high silver MOOP and low bronze premiums, HDHP plans will likely cut total MOOP exposure. And the tax benefits, which the U.S. tax code ladles onto those with enough income to save significant amounts, are substantial. You might call them quadruple benefits. The funds deposited in an HSA, up to $3,850 for an individual and $7,750 annually for a family plan

reduce taxable income (as an above-the-line deduction from Adjusted Gross Income);

increase Advanced Premium Tax Credits in the marketplace by reducing income;

accrue interest and/or capital gains tax-free while held in the account; and

can be withdrawn tax-free to spend on allowable medical expenses.

Funds accrued in an HSA can be used throughout the owner's lifetime to pay medical expenses, including Medicare premiums. Louise Norris has a complete lowdown.

* * *

Well, this did not really end up being a "guide" likely to used while shopping for insurance, did it? Pretty ungainly for that. Still, I hope it's useful as an anatomy of a market that's a peculiar offspring of American political ideology, political dysfunction, generous funding, and creative adaptation. Somehow I felt compelled to put pricing factors that should shape the application and choice in one spot -- leaving aside the vital matter of provider network adequacy, which pushes many who know they need significant care into plans priced well above the lowest at each metal level, or into suboptimal metal levels. That's a whole other story, and maybe a bigger one.

---

* One nonexpansion state, Wisconsin, offers Medicaid to adults with income up to 100% FPL, as opposed to the 138% FPL threshold in expansion states. Because ACA subsidy eligibility begins at 100% FPL, Wisconsin has no "coverage gap" -- those who lack affordable access to other insurance are eligible either for Medicaid or subsidized marketplace coverage.

** Washington, D.C. extends Medicaid eligibility to 205% FPL. New York and Minnesota run Basic Health Programs -- Medicaid-like low-cost programs -- for residents with income in the 138-200% FPL range, as well as for legally present noncitizens who are time-barred from Medicaid eligibility. Connecticut extends Medicaid eligibility to parents with incomes up to 160% FPL.