Three cheering facts about the ACA marketplace in 2023

Boosted subsidies, more low-cost gold plans and raised FPL levels should help many enrollees, while long-term premium stability has helped the Treasury.

HealthCare.gov posted available health plans and premiums in the ACA marketplace for 2023 this week. Many state-based exchanges also have their menus up. (So does commercial broker and Direct Enrollment platform HealthSherpa, the easiest place to check out plans and prices throughout HealthCare.gov states.)

On the whole, the markets are in good shape, albeit with some lead linings to bright puffy clouds. The ARPA-enhanced subsidies that boosted enrollment by 21% last year are still in place, thrown a three-year lifeline by the Inflation Reduction Act (though with Republican control of at least one house of Congress likely, their ultimate future is uncertain). Not only was enrollment up in 2022; retention was also good, at least through first payments, probably boosted by radically lower subsidized premiums (95% of those who selected plans in Open Enrollment had effectuated enrollment in February).

Gold plans will be more affordable to more enrollees than ever this year, a boon to higher-income enrollees who don't qualify for the strong Cost Sharing Reduction that attaches to silver plans at incomes up to 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Insurers have newly entered several markets, though new offerings are more or less offset by the exit of Bright Health from 17 states (Louise Norris runs through market entries and exits nationwide here).

Three salient features of the national marketplace are outlined below. A caveat is that the first two deal in broad averages: prices and offerings vary widely by state, and often by county or even zip code.

1. Long-term premium stability, 2018-2023

Coincident with the election of Trump, the ACA marketplaces were roiled to the point of questionable sustainability by premium increases averaging 20% in benchmark silver plans in 2017 and 34% in 2018. Premiums for 2017 underwent a major and expected correction that had nothing to do with Trump, as insurers with three years' experience in a totally new market (launched in 2014) recognized that they had seriously underpriced plans, and as a three-year federal reinsurance program enacted to stabilize that new market expired. In 2018 the looming threat of ACA repeal, reinforced by the Trump administration's legislative assaults, gave insurers cause and license for a second massive boost.

Thereafter, premiums stabilized. Insurers overshot with their increases in 2018, and the ACA requirement that they spend at least 80% of premiums on clinical care and quality improvements triggered large rebates to enrollees ($1.7 billion in 2019, $1.3 billion in 2020, and $1.5 billion in 2021*). Trump's heaviest intended blow to market stability -- his abrupt cutoff of direct CSR reimbursements to insurers (payments mandated by ACA statute but never appropriated by a Republican Congress) -- actually (and predictably) boosted enrollment in 2018 and years following, as CSR was priced directly into silver plans (the only plans with which CSR is available), creating discounts in bronze and gold plans (since premiums and subsidies are set to a silver benchmark). That pricing-in of CSR came to be known as silver loading.

Enrollment s held steady until the incoming Biden administration massively boosted subsidies -- i.e., payments to insurers -- in the American Rescue Plan in March 2021.

The net effects on the past six years of premiums o

f all this political sturm und drang are shown below, courtesy of data from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

Premiums for the lowest-cost silver and gold plans and benchmark (second-cheapest) silver plans are lower on average in 2023 than in 2018, while lowest-cost bronze premiums are essentially unchanged. (As competition is most intense at the lowest price points, since most enrollees select low-cost plans, total weighted average premiums may tell a somewhat different story.)

As 90% of marketplace enrollees are now subsidized, low premium increases are a boon mainly to the federal treasury. What matters most to enrollees (besides the overall generosity of the premium) is the spread between the benchmark silver plan (for which they pay a fixed percentage of income) and other plans they might want. From that standpoint, the sharp reduction in benchmark silver premiums relative to lowest-cost silver and lowest-cost bronze premiums is actually a negative for enrollees (though more than offset by the ARPA/IRA premium boosts).

2. Cheap gold in Texas

On the upside for enrollees, however, is a large reduction in the average spread between benchmark silver plans and lowest-cost gold plans, from 9.3% in 2018 to just 3.5% in 2023. That's in large part a result of a handful of states requiring insurers to price silver plans either in strict proportion to their average actuarial value (generally boosted well over gold's 80% by the CSR that attaches to low-income enrollees' plans) -- or, more radically, to price silver plans on the assumption that almost no one with an income over 200% FPL (the eligibility threshold for strong CSR) will buy silver if gold plans are cheaper (as they should be, since their actuarial value is lower on average). That means pricing silver plans at a platinum level, since CSR does in fact make them platinum equivalent at incomes up to 200% FPL). (In 2023, when premiums rose by about 4% per KFF, the spread between benchmark silver and lowest-cost gold shrank from 5.5% to 3.5%.)

New Mexico took that more radical path in 2022 -- and more than two thirds of enrollees with income over 200% FPL selected gold plans. Remarkably, Texas of all states has followed suit in 2023, having enacted a law last year requiring the state insurance department to price gold plans well below silver. That a radical Republican state legislature and governor would take this step, after ten years of rooted hostility to the ACA, has got to be among the most politically countertrend stories of our time. It's due in the first instance to a pair of politically conservative actuaries, Greg Fann and Daniel Cruz, who have pitched strict silver loading to a number of state insurance departments and legislators, and to receptive key actors in both parties in Texas.

David Anderson flagged the results in Harris County yesterday. The lowest-cost gold plan is priced 15% below benchmark. At an income of $28,000 per year (206% FPL), a single 40 year-old get can the lowest-cost gold plan for free. A 60 year-old with the same income can choose among three free gold plans.

Free gold offered that far up the income scale does create a selection problem for those with incomes in the 150-200% FPL range, where CSR boosts the actuarial value of a silver plan to 87%, compared to 80% for gold. The higher value of silver in this income bracket is most salient in the annual out-of-pocket (OOP) maximum, for which the highest allowable for a CSR silver plan at this income level is $3,000, compared to $9,100 for all other metal levels. To get the higher value silver coverage, though, a Houston resident in this income range will have to pay a significant premium, topping out at 2% of income, or $45/month for a solo enrollee (silver plans are free at incomes up to 150% FPL).

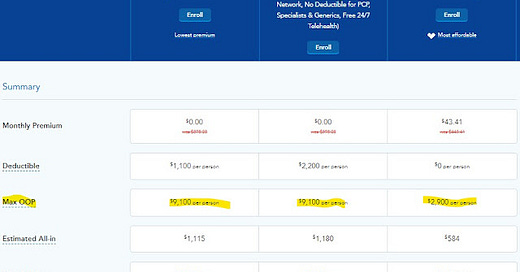

Here's how the choice plays out between the two cheapest gold plans and the benchmark silver plan for a 40 year-old Houston individual with an annual income of $27,000 (199% FPL). The first two plans listed are gold; benchmark silver is on the far right. Note that Ambetter dangles a $0 premium for the silver plan, which is not typical for that brand at this income level -- or hasn't been in the past, anyway. But the key difference, again, is in the OOP max.

$9,100 is a huge exposure at this income level. Most enrollees won't get anywhere near that OOP max. But insurance is about risk management.

Part of the problem in Houston is that as in many markets, cut-rate insurer Centene, operating under the Ambetter name, has undersold the competition enough to grab both the lowest-cost silver and benchmark silver positions, and priced them within pennies of each other. A lowest-cost silver plan that's significantly cheaper than the benchmark plan might make that silver premium -- which is very low by pre-ARPA standards but still substantial at this income -- more palatable.

New Mexico had a problem with cheap gold at low income levels last year. About a third of enrollees with income low enough to qualify for strong CSR (with 87% or 94% AV) chose gold plans -- partly because of flawed guidance from the state marketplace, bewellnm. This year, the state has added its own "wraparound" subsidies to CSR silver plans this year and dubbed them "turquoise"-- creating a deal that no one should refuse.

HealthCare.gov, which Texas uses, has somewhat better signposting about the value of CSR than did bewellnm last year. But if you don't respond to a prompt to view silver plans first, your first site will be a long line of free gold and bronze plans.

3. Inflation raises Federal Poverty Level and OOP caps

Inflation drove a major jump in the Federal Poverty Level for 2022 (operative in the ACA marketplace for 2023 enrollment) to $13,590 for a single person, up 5.5% from the year prior. That jump lowers premiums for subsidized enrollees whose income didn't increase as fast as the FPL. But it's a raised eligibility bar for low-income people in the 11 states that maintain a "coverage gap" because they've refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion. In those states, most adults with income below the 100% FPL eligibility threshold for subsidized marketplace coverage are not eligible for Medicaid (which the ACA extended to adults with income below 138% FPL in states that have opted in), and so get no help paying for coverage at all. Now they must estimate an income above $13,590 for a single person ($18,310 for two people, $27,750 for a family of four) to qualify for subsidies, up from $12,880 last year.

As I've pointed out elsewhere, the income estimate required by the ACA application allows for considerable wiggle room, and an employed person's good-faith estimate of an income in excess of the 100% FPL threshold will not lead to disqualification or clawback if actual income falls short of the threshold. Simple awareness of the threshold may enable some people to avoid disqualification for low income -- but many if not most low income unassisted applicants have no idea that there is a threshold. CMS has somewhat eased this path by extending year-round enrollment to applicants with estimated income below 150% FPL -- so a spike in hourly or seasonal income at any point in the year may facilitate enrollment in zero-premium CSR silver coverage. Still, the raised FPL bar will doubtless shut some people out. Conversely, though, more people in the 38 expansion states and D.C. will qualify for Medicaid.

The highest allowable out-of-pocket maximums also went up considerably this year. For plans other than HSA-compatible plans and CSR silver, the OOP max rose from $8,700 to $9,100 for an individual (in 2014, it was $6,350). OOP maxes for HSA plans rose from $7,050 to $7,500. For CSR silver plans at incomes up to 200% FPL, the increase was from $2,900 to $3,000, and for CSR at the 200-250% FPL income level, from $6,950 to $7,250.

In the ACA marketplace as in the employer-sponsored market, out-of-pocket costs have risen faster than premiums. For ACA beneficiaries -- in Medicaid as well as the marketplace -- those increased costs have been partly offset by states belatedly opting into the Medicaid expansion (as 14 have done since January 2014); a gradual increase in silver loading effects, which has boosted gold plan enrollment from 4% in 2017 to 10% in 2022; and the ARPA subsidy increases, which have made high-CSR silver coverage more affordable for those with incomes below 200% FPL. Conversely, though, discounts in bronze and gold plans created by silver loading have pushed more low-income enrollees out of high-CSR silver, and more often into bronze plans than gold. ARPA subsidy boosts only partly reversed the reduced high-CSR takeup.

Chat among ACA market watchers on Twitter last night indicated that while fewer states are offering gold plans priced below benchmark this year, more enrollees will have access to those plans, since gold below benchmark is more widely available in Florida and Texas this year than previously. Since silver loading was kicked off in 2018 by Trump's late-2017 cutoff of direct payments to insurers for CSR, the effects have been haphazard and partial. Prior to Trump's cutoff, analysts at HHS, the Urban Institute, and CBO had forecast the effects of silver loading if such a cutoff occurred, and all expected gold plans to be priced consistently below silver. That hasn't happened, as a large plurality of marketplace enrollees qualify for and enroll in high-CSR silver -- and perhaps more importantly, CMS's risk adjustment formula favors silver plans. Insurers are therefore inclined to underprice silver. The ACA requires that they price plans in strict proportion to their actuarial value -- but as noted above, only a handful of states enforce this, to greater or less degree. Were CMS to require such strict silver loading -- fixing risk adjustment so that insurers were not disadvantaged by selling more gold and bronze plans -- gold plans would be consistently priced below silver nationwide. David Anderson and I made the case in Health Affairs last year that CMS should do this.

Here's hoping for expanded enrollment and good retention in 2023. When the Covid-induced Public Health Emergency ends, and with it a three-year moratorium in Medicaid disenrollments, the marketplace will stand as a potential safety net for millions who will be disenrolled from Medicaid. That constitutes major challenges for the federal and state governments in communication, outreach, and administrative functioning. Stay tuned.

--

* Rebates are based on a three-year average of the insurer's Medical Loss Ratio (MLR)

Photo by Kampus Production